During the final minutes of Edna & Harvey: Harvey’s New Eyes, I made the connection.

During the final minutes of Edna & Harvey: Harvey’s New Eyes, I made the connection.

Earlier this year, Spec Ops: The Line focused on the role of player agency. It took advantage of the completionist attitude games have trained us to adopt. Games are made to be finished. Spec Ops challenged that.

It’s a question tied to the medium, not to the individual game. Harvey’s New Eyes isn’t about a rescue mission in the middle of a Middle-Eastern war. It’s an adventure game that asks the same question in a different wrapper. Beneath its colorful exterior is a thesis on the divide between avatar and player, a morbid tale of free will.

On the surface, Harvey’s New Eyes is the story of a young girl trying to escape life in a convent. She’s tired of the dogma, and the chores. It’s the classic struggle between children and adults. The adults force their own values on the children, and the children rebel. Lilly is the anomaly. She’s quiet and speaks in fragmented words. She’s the puppet, and you’re pulling the strings.

You’ll order her to pick up items, trespass, talk to psychopaths, drink alcohol, and murder to solve puzzles. Harvey’s New Eyes won’t dissuade you from your ruinous actions. You’ll click to proceed to the next horrible thing. Over and over. And you’ll do it because it’s the only way to progress, not necessarily because you believe it’s right.

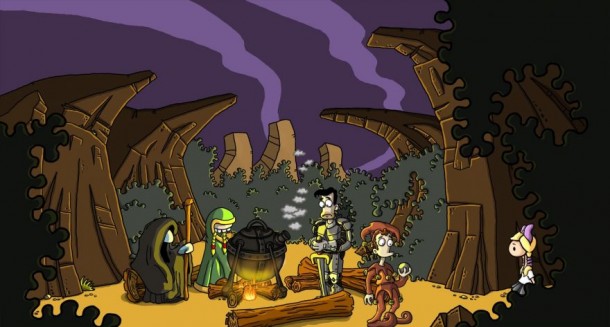

Then, roughly halfway through, Harvey’s New Eyes severs your bond with Lilly, and restricts her free will. Abilities like using fire, sharp objects, and lying must be reobtained by traveling to and from limbo, an alternate version of reality. These segments only offer stranger scenery. They’re fun to look at, but they don’t alter the game’s rote puzzle design. Someone will need a specific item, and you’ll find it for them. They’ll reward you with piece to another puzzle, and the cycle continues.

Then, roughly halfway through, Harvey’s New Eyes severs your bond with Lilly, and restricts her free will. Abilities like using fire, sharp objects, and lying must be reobtained by traveling to and from limbo, an alternate version of reality. These segments only offer stranger scenery. They’re fun to look at, but they don’t alter the game’s rote puzzle design. Someone will need a specific item, and you’ll find it for them. They’ll reward you with piece to another puzzle, and the cycle continues.

Lilly can only overcome one restriction at a time, forcing you to juggle between them as you test for solutions. With the amount of clues the game provides, the switching mechanic avoids becoming tedious. You’ll always know where and when to use them just by how blatant the characters spell it out for you.

The bulk of Harvey’s New Eyes’ characters suffer from poor voice acting. When it doesn’t sound forced, it sounds over-rehearsed. The most offensive of them is the game’s narrator. His extended commentary on every object you click drags the game down, and only picks up in the final few hours. There’s a severe lack of nuance to the characters you meet in the second half of the game. A few of them feel like they have an interesting story to be told, but the game tramples over them in its rush to the finish. Entire subplots are sped through and unresolved once you reach the game’s conclusion. It leaves the game feeling overstuffed with ideas.

Harvey’s New Eyes makes it easy to forget its shortcomings when you start to question your own actions. During your search for the next step in your escape from the convent, you’ll find a girl sitting on a swing, dangling over a cliff. The swing is a attached to a tree you need to get rid of. After some searching around, you’ll be given a chainsaw. You’ll quickly realize what must be done, and how it will affect the girl. Never will the game make that connection for you. The only way out is to stop playing. To not cut the tree down, and to save the girl from the fatal fall. It’s one of many powerful moments the game leaves for you to interpret. And like Spec Ops, it’s just as easy to miss as it is to notice.

Harvey’s New Eyes makes it easy to forget its shortcomings when you start to question your own actions. During your search for the next step in your escape from the convent, you’ll find a girl sitting on a swing, dangling over a cliff. The swing is a attached to a tree you need to get rid of. After some searching around, you’ll be given a chainsaw. You’ll quickly realize what must be done, and how it will affect the girl. Never will the game make that connection for you. The only way out is to stop playing. To not cut the tree down, and to save the girl from the fatal fall. It’s one of many powerful moments the game leaves for you to interpret. And like Spec Ops, it’s just as easy to miss as it is to notice.

It’s hard to tell if Harvey’s New Eyes is aware of its lofty ambitions. Its deconstruction of what it means to have free will in games is, at times, more effective than Spec Ops. It’s just as unsettling as you start to think twice about what you’re forcing Lilly to do. But where Spec Ops failed, so does Harvey’s New Eyes. Its unnerving commentary on the nature of player agency doesn’t save it from being a mediocre game.

No Comments