The minds over at With a Terrible Fate argue that game canons should be a thing—and no, they are not elitist gate keepers: a sum-up of the panel.

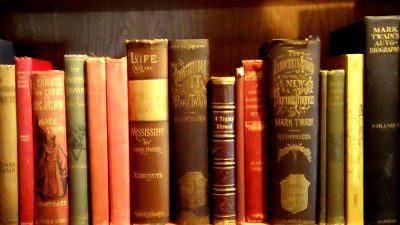

It’s safe to say that if you’ve taken a literature class, you have read a piece of classic literature. They are often written into the curriculum of public school systems or taught as entire classes at the college level. Often, these classics fall into what is called a literary canon. And often, we view these classics as pedantic gate keepers, preventing new literature from entering in the system is what is read and analyzed. A vampire sucking the creativity from English classes everywhere.

As an English teacher, I do have a problem with the way the canon is approached in school. Beginning instruction with choice novels to inspire a love and narrative of reading should occur prior to handing a student Chaucer or Shakespeare. However, if used correctly, canons serve a purpose in the literary world. They are not truly meant to gatekeep. They are meant to reflect. By connecting literature in canons we witness storytelling and common elements that reflect the history and trends of a time period. They create reference points for understanding (e.g., “I want to tell a frame narrative story—let’s reference Chaucer’s the Canterbury Tales.”) They do all of this, because, in reality, nothing truly exists in a vacuum. All it takes is a reading of James Joyce to see his connections to other authors. His inspiration swelled from Shakespeare, Yeats, and Irish Mythology. We all borrow content—and this is especially true in writing. We are inspired and grow from the content we devour, just as interacting with others molds our own identity.

The importance of a literary canon spans the thousands of years in which literature has existed, and despite the novelty of video games as a mode of art and media the academic minds of With a Terrible Fate argue that its time we talk about a gaming canon. As an academic and gamer, I agree with them. Video game discourse is new and worthy of exploration, and the creation of canons towards that discourse can only help the process of analyzing games.

But why do we need to analyze games? While that sounds boring, the more we examine games, the more we determine what makes them effective.

The more we ask questions like: How do genres work? What is this game’s function or goal? Why is this more valuable or effective as a game than a movie? … the more we figure out about what makes certain game tick based on their intended purpose. This sort of inquiry ultimately creates a cycle of community, media, and developer feedback that ties directly into game development

One current argument is that game reviews contribute to the analytical growth of the industry; however, the problem in that claim is that they do not really offer a critical discourse around games. While reviews do indeed serve a purpose, more often than not, they (along reviews of any kind, really) tend to be heterogeneous. Instead of focusing on the idea that a game’s value is subjective based on authorial intention and player rationale, it only focuses on a singular value system (e.g., Does the game play well? Does it have a good feel?). The beauty of games is that they can serve multiple purposes: entertainment, education, narrative, problem solving. They vary in player interaction (e.g, silent protagonist, 1st person, narrative choice). Placing and analyzing games in canons allows us to address the multifaceted nature of games in a way that better serves their initial creation as well as future development. By looking at what made a game like The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time a “classic” we can determine trends that may determine the success of other titles.

There is still a long way to go in terms of developing game canons. There must be groupings and trends divided among genres and a general consensus as to where those will fall. However, a discourse around the idea of it is where we begin, and this panel was the start of that.

![[PAX East Panel] The Video Game Canon](https://www.sidequesting.com/wp-content/uploads/vids.jpg)

No Comments