I have a huge thing for stealth games; anyone who knows me can attest to this. Over the years I have dumped more hours into the various entries in Konami’s Metal Gear Solid series than any sane person probably should. When I heard that Mike Bithell, developer of the astonishingly charming Thomas Was Alone not only shared that pure love for the genre, but was embarking to make one of his own, I was more than a little intrigued.

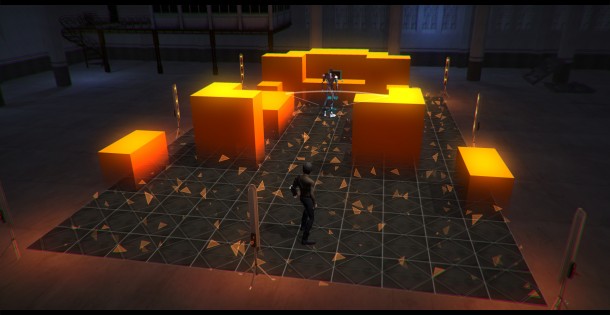

Bithell has cited Metal Gear Solid (more specifically, VR Missions) as a major inspiration for Volume from very early on in the development process, and that influence is incredibly easy to see. From the bite-sized, self-contained structure followed for each of the game’s 100 core levels, to the simplified, virtually simulated design aesthetics.

That inspiration isn’t a bad thing, though, and was used more as a base and jumping off point than a recreation. Much of Volume feels more like a puzzle experience than the “Tactical Espionage Action” of its spiritual predecessor, relying more on your wits and how to effectively use the game’s assortment of gadgets to get to the end goal.

Volume throws you right into the shoes of near-future Robin Hood, apparent revolutionary and internet broadcaster Robert Locksley. With the help of a talkative and forgotten AI and a tool known as “the Volume,” Locksley is able to simulate virtual areas and carry out mock heists on important locales owned by Guy Gisborne (voice by Andy Serkis), tyrannical and businessman ruler of a new post-war dystopian England, as well as his many grimy associates. The simulated heists aren’t just for Locksley’s own personal edification, however, as he live-streams these sessions out in an effort to influence the downtrodden masses to “take back what’s theirs” and hopefully turn the tide in an apparent classist struggle.

The game’s story beats are told through a series of brief interstitial conversations and through various email pickups throughout levels. It’s a novel way to handle the story, but if you’re playing the game as I did — in a furious race against the clock — they can be easy to miss or seem as a bit of a chore. However, going back and collecting them helps paint a much better picture of the dystopian England outside the four walls of Locksley’s warehouse.

Once into the actual meat of the game you’re exposed to hours of creeping around corners, examining environments for traps and sneaking opportunities, following guard patrol patterns and figuring out how you can best use the tools at your disposal to get in and out, undetected and in as little time as possible.

For such a simple design and visual style, the game looks fantastic. Watching the walls, guards and various accoutrements “rez in” at the start of each level never gets old, and the shifting color pallet helps make each level feel fresh, rather than a retread. This feeling of progression and discovery is bolstered by being drip fed new mechanics and techniques as the game marches forward. Learning how to blend new techniques into the core mechanics that you’ve spent hours honing is hugely rewarding, and a wonderful design decision.

The game’s controls are tight and straightforward, and make employing all of those techniques second nature once you’re well enough acquainted with them. There were a good handful of times that I was angered by the game and had to walk away due to frustration only to come back later, however, I never felt like my failings were due to shortcomings on the game’s part. More often than not, my frustration was caused by over-thinking a specific aspect of a level or not utilizing all of the tools I had at my disposal, and in retrospect the objectives and paths are often clear from the start, albeit sometimes difficult to accomplish.

All of this is not to say that the game is without fault, though. While I appreciated there being more room for error by the inclusion of ample shadows, outcroppings or closets to hide in, the game’s extremely generous checkpointing took away much of the challenge for what would be otherwise a pretty difficult situation, especially considering how resetting to a checkpoint also puts guards into their default pattern. In the more challenging areas of the game I found I could viably run in, grab what I needed while alerting guards, only to run off to a checkpoint and instantly reset with no time penalty and having taken the guards off of alert. I would often not even bother trying to sneak past enemies after enough frustration.

I should also note that the introduction shadows were a great idea in theory, but by being even partially covered by one renders you invisible to a patrolling guards, and you can be almost touching guards as they roam on unaware of you.

These faults hardly diminish the experience, though, as Volume more than makes up for them with clever level design, decent writing and a fresh take on espionage melding together old and new stealth mechanics. Sure, you can try and just sneak your way through a level, but you won’t get far without figuring out what enemies are ahead and how to get by them, like finding the “Mute” tool to run swiftly and silently through a room filled with alarms and guards, or hiding from line of sight while you throw a remote-detonated noisemaker behind a slow-moving but far-seeing “Archer” enemy type, to dart around them.

Sure, the game has its faults, mainly in the departments of an extremely rudimentary enemy behavior system and checkpointing that can be exploited six ways from Sunday, and an inability to pan across an environment to formulate a better plan of attack, but I found more than enough to love about the game’s interesting story and new take on a genre that I hold very near and dear to my heart. I only wish that it was available on a portable platform at launch, as its bite-sized design would lend itself perfectly to that form factor. The Vita version can’t get here soon enough!

Volume was reviewed using a pre-release Steam code provided by the developer.

No Comments