Kaiju Review is a feature series on SideQuesting in which several noteworthy kaiju monster movies are reviewed and reflected upon. They are not scored or rated.

“This is unbelievable! Yes, unbelievable! But the unbelievable is happening before our eyes!”

The year is 1954. A reporter stands on the terrace of a Japanese steel communications tower, screaming the words into a microphone. In front of him a calamity is taking place, the size and scale of which has been unseen in a decade. Explosions, fires, and chaos rain. Radioactivity reigns. But this isn’t another atomic bomb dropped on an unsuspecting city; this is Godzilla. This is worse.

This is unbelievable.

The original Godzilla (Gojira, in Japanese) was hardly a monster movie by today’s standards. Yes, it centered around a giant prehistoric beast rampaging through a helpless city, but its focus was more about the societal sea change that was taking place. The end of World War II was a key moment in human history, when typical warfare was replaced by terrifying new weapons of mass destruction that knew no bounds. No longer could war be controlled, nor the weapons be known how to be dealt with. Warfare wasn’t confined any more, and could and would spiral out of human control.

To the Japanese, what the US unleashed on 6 August 1945 was itself a monster.

Nearly ten years later, Japan was still healing. Its welfare had taken a horrific hit, but the country’s culture and society were making incredible rebounds. Art and technology were leading the way, and it was just a matter of time that the two would come together, sparked by political statement. And that’s exactly what Godzilla represented: a political outcry against the monster of weaponry that had been unleashed.

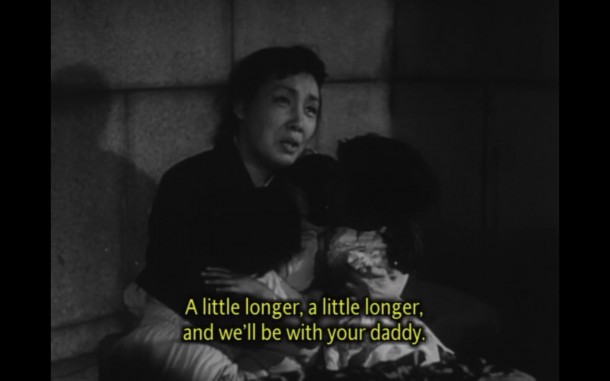

The film is intentionally dark and foreboding; Director Ishiro Honda and Cinematographer Masao Tamai play up the black & white film, cranking up the contrast to noir levels and pushing the beast several more shades into darkness. It’s also no surprise that all of Godzilla’s raids happen at night, adding to the inherent human fear of darkness and lack of light.

Godzilla is the darkness, humans are the light, consistently failing at stopping him. Each time something light or happy or positive is happening on screen, Godzilla appears to stomp it down — sometimes quite literally. In one scene, partygoers on a brightly-lit boat enjoy an evening full of laughter and dance, shattered by the giant dark form of Godzilla appearing in the night’s water in front of them.

His design amplifies this. He’s over 50 meters tall, with a massive tail and human-like upright stance. His stoic face paints him to be a walking Colossus of Rhodes, almost mechanical in his actions. That’s what makes him ever more terrifying; it’s as if he, like the atom bombs before him, is programmed to destroy humanity.

That’s where the politics v science v religion v man battle becomes the centerpiece.

Yes, Godzilla was created to show the horrors of atomic warfare and the bombings — which is why it was heavily edited when brought to the States, adding American actor Raymond Burr to fill in some of the narration — but there is a lot of power in how they approached the subject. This is a film about the science, not so much the foreign policy, of man’s attempt to control his environment and each other. Great technological advancements happen often because of war, and with atomic power becoming ever more present in society it was apparent even in 1954 that it could be abused, even running out of control. Much like The Walking Dead just happens to take place during a zombie outbreak, this story of man happens to take place during a dinosaur outbreak.

Godzilla is the after effect of man’s strive for dominance over science. The government calls in scientists and paleontologists to figure out what’s happening, and they run smack into the religion of the island of Odo, who have revered Godzilla as a deity over the centuries. God has come to destroy man for his sins, they believe. Accentuating this is the human aspect, a love triangle between actors that themselves represent religion science and politics.

But the subtleties of all of this are trumped by the awe we feel when Godzilla appears on screen each time. He’s huge, he’s terrifying, and he’s magnificent. We love him and we fear him, and yet a part of us feels like we’re a part of him. He’s terrific to watch as he slowly lumbers through Tokyo like a force of nature, destroying buildings and crushing Man’s hopes at every opportunity. Explosions, electric shocks, fires and fire-breathing! Everything is here to scare us back into our bunkers.

And, when humanity finally triumphs, killing Godzilla with science and sacrifice (and an “oxygen bomb”), we’re almost saddened by the death.

Sixty years later, Godzilla is still a joy to watch. Yes, there are aspects that have become mainstay in monster films since then, and the series’ films became incredibly hokey during their longevity, but there is still magic in the first film that hasn’t been duplicated very often since.

Godzilla is still unbelievable.

This review is based on a digital retail copy of Godzilla viewed through the writer’s Amazon Prime Instant Video account

No Comments