(THIS IS YOUR FINAL WARNING. ALL KINDS OF SPOILERS AHEAD. DO NOT READ THIS UNLESS YOU HAVE COMPLETED THE GAME.)

I don’t know if it happened and I missed it, but I honestly expected to hear a stray “would you kindly” at some point in Columbia. It wasn’t necessary, but it would have been nice. Instead, I got sent to Rapture for just a moment. Or, at least, one incarnation of Rapture. But we have a lot to learn about ourselves before we get there.

Bioshock Infinite is the kind of game that starkly illustrates the difference between what’s in a game and what a game is about. The game contains unflinching portrayals of racism (both explicit and casual), the kind of monstrous civil religion that would make the Establishment Clause have an anxiety attack, and swimming pools-worth of digital blood. What is it about, though? Just like the original game, it’s about choices.

But, just like the original game, it’s not the choices one would expect. Bioshock hinges critically around the fact that, as gamers and as people in the real world, we don’t actively control as much of our lives as we think. All it takes is a soft “would you kindly?” to win our compliance. We didn’t even need to be brainwashed. Infinite’s take on free will is that, even in circumstances in which we act most freely, what we do does not mean what we think it does.

As Booker arrives in Columbia, he is given the false choice of being baptized to enter the city. Both Booker and the player know that refusing this baptism results in nothing more than having a group of very (very) Aryan new arrivals to the American Eden staring blankly at you. Accepting the baptism means getting closer to saving Elizabeth.

The baptisms in the game are especially appropriate. In many Protestant denominations the act of immersion baptism is a metaphor for death and rebirth, and not ‘merely’ a symbolic cleansing. The first baptism, at the beginning of the game, is used in a more traditional sense in which the aspirant dies to the world and is reborn in purity. The second baptism, the one Booker accepts much more willingly, results in literal death to prevent the inevitable corruption of his own soul.

Bioshock and Infinite are about the illusion of choice and consequence in real life as much as they are in video games. It seems like Booker sacrifices himself (or, looking through a Biblical lens, allows Elizabeth to sacrifice him) to prevent himself from becoming Comstock, but given the previous ten minutes of exposition should we believe that is the case? Does drowning in a baptismal stream retroactively prevent Booker from giving his magic daughter away to an angry religious zealot? Elizabeth demonstrated the eponymous number of realities which may contain Comstock, or not, or a Comstock obsessed with Oreo cookies instead of George Washington, or a Comstock who gets a brain aneurysm while forcing a morning constitutional.

In this, I think, we find the subtle substance of the argument of choice: our choices are for us, not others. Booker didn’t save anyone else, really. He is powerless against infinite realities. His powerlessness is not due to any failing of his own, but by the abyssal revelation of doors opening up to places to which they have no claim. This singular Booker, the one we’ve been hanging out with for the last twelve hours, made a choice that will necessarily be divergent from all the other Bookers, and nothing he could ever do would prevent that. But his actions obviously will not reverberate across all realities.

Such fatalism is not without precedent in postmodernism. That was a joke; postmodernism wouldn’t exist without fatalism. Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five introduces us to aliens called Tralfamadorians who viewed all of time and space as a completed work which can be freely navigated, not a stream of sequential experience. In describing this to the protagonist Billy, they explain that viewing all things that humans perceive as past, present, or future at once is like looking at a mountain range: the current presence of one peak does not preclude the existence of all other peaks. Everything exists at once.

They also tell Billy they know how the universe ends. They test a new spaceship and upon ignition it fails, resulting in the end of all things. When Billy asks them why they don’t stop it, they do what aliens do to indicate a shrug and tell him there is nothing to be done, because it has already happened and is happening and will continue to happen.

“Dies, died, will die,” say the marvelous Luteces. In joking about the subjective perception of time, they manage verb tense jokes in almost every interaction. And, in a way, verb tense jokes themselves are a form of time travel. All things are concurrent, and the only thing that makes them seem the way they are is our perspective. If we accept this, then the only thing our choices affect is our own perspective. We can’t save anyone aside from ourselves.

Booker couldn’t even save Elizabeth. His only choice was to choose to save himself, or not.

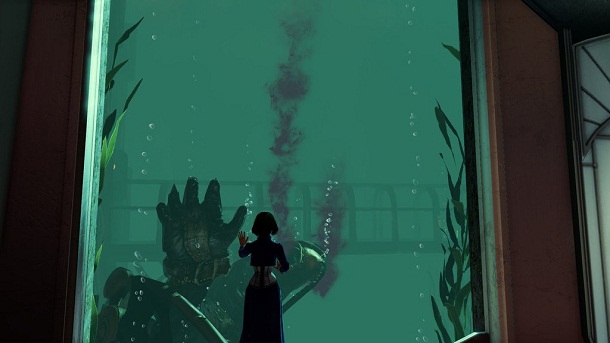

As his vision blurs and sounds fade, the fact that his final act of self-interest was to be submerged in water for the rest of his life is probably a better prologue to Bioshock than visiting Rapture.

4 Comments