It would be easy to say that Dokuro is the Darksiders of puzzle-platformers. It clearly draws upon ideas used in games like Ico, Okami and even Escape Plan, another popular Vita puzzler. All of that is true, but it ignores that Dokuro has another, more primal identity.

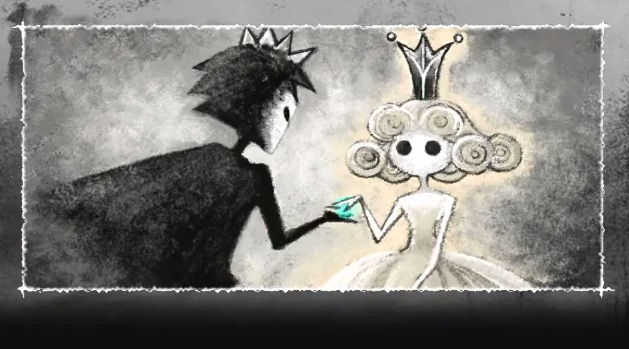

Dokuro is a fairy tale.

The game tells the age-old Beauty and the Beast story we’ve all seen a hundred times. In this case, the titular Dokuro is a small, invisible skeleton in the employ of the Dark Lord. At the outset of the game, the Dark Lord kidnaps a nondescript princess to become his bride. Dokuro decides he isn’t having any of that and chooses to help said royalty escape the evil lord’s fortress.

This quixotic conceit is key to gameplay, as the game is structured as an incredibly lengthy string of stages in where the goal is to get the princess from point A to point B.

Yes, this means that Dokuro is technically based on that most hated of gameplay tropes, the escort mission. Don’t let that scare you off, as in practice this is actually a puzzle-platformer as you structure each stage on the fly to create a path for your royal beau cross. This is accomplished in the traditional ways — pushing blocks, flipping switches, killing enemies, etc. — as well as by using several sets of magic chalk.

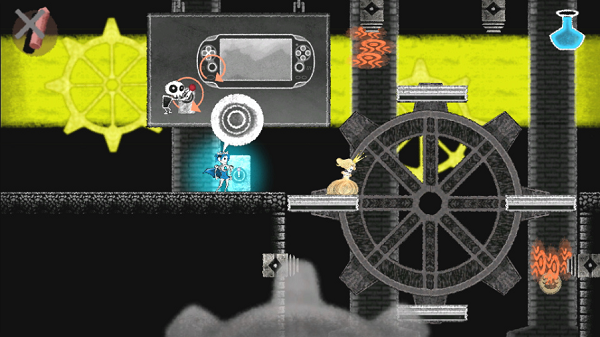

Chalk is very important in the world of Dokuro. Using its multiple, magical variants to draw across the Vita’s touchscreen is a necessary component in the solutions to most puzzles. However, chalk is also the focus of the game’s aesthetic.

Dokuro features the distinctive style of a world made from chalk lines and slate. Enemies explode into puffs of chalk dust once dispatched and absolutely everything looks as though it was drawn on a classroom blackboard.

It’s a very unique design, as well as crucial to the game’s whimsical nature. Unfortunately, it’s also very static. The developers clearly didn’t spend a lot of time actually animating their beautiful art, and the results are bittersweet.

Most of the character animation during gameplay is just sprites being wiggled back and forth. Meanwhile, the cutscenes don’t even feature that as characters simply slide across the screen, completely stiff. It’s arguable that this was done to maintain Dokuro’s picture book feel, but it often feels cheap or lackadaisical on the part of the artists. A bit of extra oomph in this area could have pushed the game’s style beyond “charming” and straight into “unforgettable” territory.

As it is, Dokuro is distinctive, but less impressive than it could be.

The game’s difficulty, on the other hand, will likely leave quite an impression on anyone that actually manages to complete the game.

Dokuro‘s puzzles can get challenging. Incredibly challenging. Like any good puzzle game, some of the most difficult levels will start off looking deceptively, only to become pixelated rage drugs after you’ve slammed your primate brain against them for 20 minutes at a stretch. The game also feeds the player a slow, constant drip of new ideas and mechanics throughout its lengthy campaign. Because of this, that challenge never gets stale and never stops being apparent throughout the very lengthy campaign.

Unfortunately, Dokuro doesn’t always rely on tickling the players brain as much as it should.

Certain stages, especially in the game’s penultimate stage, rely heavily on combat. This is handled by allowing our hero Dokuro swap between his double-jumping “dead” form, and his more temporary and combat-ready “prince” form.

First off, it should be noted that the default way of switching between forms is mapped to rear-touch controls, and should immediately be swapped in favor of the much more reliable R button.

That’s not the primary issue with combat, however. That dubious honor falls to the fact that combat in Dokuro just isn’t very fun on its own. Fighting is comprised entirely of mashing the square button until an enemy dies.

That’s it. It’s not fun, interesting or challenging. It’s also thankfully not incredibly commonplace. When it does feature, it’s usually used to slow you down in concert with some sort of timed piece of the level. Other times, it’s used as a means of keeping you glued to a specific spot in order to protect the princess. Very rarely, however, it seems to exist simply as an irritating obstacle standing between you and your destination. When it is, it can really kill the momentum and make otherwise simple puzzles a chore. It’s almost as if certain levels were deemed to easy by some manager somewhere, and enemies were thrown in at the last minute to create the illusion of a challenge.

Mercifully, this isn’t the case with the game’s very creative boss fights. When it comes time to lay the hurt on a boss’ hearty health bar, it’s still just the same button mashing featured throughout. But getting a boss into vulnerable state is usually a puzzle in and of itself. And while these smaller “puzzles” aren’t as difficult as some of the standard levels, wailing on a boss that takes up half the Vita’s screen after finding the solution makes for a decent catharsis.

And that’s what Dokuro really is. Just like a fairy tale, it is the constant build-up of tension, followed by the satisfaction of knowing that you’ve made it. From the first puzzle, to what may be the sweetest ending I’ve ever seen in a video game. Everything is going to be alright. And with the added benefit of being a video game, the player gets the added reward of knowing that they were the ones that came through in the end.

Dokuro is the sort of experience that justifies video games as a medium

This review is based on a copy of the game sent to SideQuesting by the publisher.

No Comments