Zayne Black made a game about a high school sociopath who stares at his peers’ physical features to make them self conscious and leave him alone. Zayne Black made a game about a runaway rabbit attempting to flee from evil scientists, while dodging foxes, crows, and slightly disgruntled hedgehogs. Zayne Black made a game about a dinosaur coping with a recent breakup by eating cake, who also has a jet pack.

Zayne Black made a game about a high school sociopath who stares at his peers’ physical features to make them self conscious and leave him alone. Zayne Black made a game about a runaway rabbit attempting to flee from evil scientists, while dodging foxes, crows, and slightly disgruntled hedgehogs. Zayne Black made a game about a dinosaur coping with a recent breakup by eating cake, who also has a jet pack.

Zayne Black finishes what he starts.

Zayne Black was a writer first, and a game designer second. In college he studied drama, spent his time script writing, and aspired to see his work on stage or the big screen. That was until someone from the online gaming community he frequented offered him a challenge. They claimed the “endurance platformers”, games like Super Meat Boy and I Wanna Be the Guy, took “great care and skill to design.” Black disagreed. “Prove it,” they said.

At the time, Black wasn’t new to creating games; his brother had introduced him to a program called Klik ‘n’ Play when he was 11-years-old. Klik ‘n’ Play, while primitive, teaches the basic concepts of game design. It brings imagination to life, with games that have “multiple copies of Cliff Richard’s disembodied head bouncing around the screen, and weird target-shooting games starring characters from Dragon Ball Z.” Originally aimed for educational use, it doesn’t require any programming knowledge, just the ability to drag and drop different components together. His own first game? “A really glitchy Pac-Man clone, starring the Queen…”

A week after being challenged to create a difficult platformer with no experience, Black proved his internet cohorts wrong. He used Klik ‘n’ Play’s modern successor Multimedia Fusion 2 to make Awesome Bob, a game whose only purpose is to punish the player. Every jump made too early, or fidget too far to the right, ends in death. Not a level goes by without trial and error. Few survive to see the end.

They loved it.

The appreciation he received for Awesome Bob changed his priorities. He decided to make more games.

The appreciation he received for Awesome Bob changed his priorities. He decided to make more games.

Since then, Black’s built up a lengthy list of creations. Many of them were entries into game jams — events that encourage developers to start and finish projects in a limited amount of time, usually based on a central theme. Ludum Dare, his favorite, takes place over 48 hours where games are created based on a community submitted theme, uploaded to the public, and judged. The prize: a completed game.

“I think the most important thing is that they basically force you to finish whatever you’re doing, which is, in my opinion, the most important part of creating anything. Sooner or later, you have to learn how to finish something, no matter what – nothing is more important to your growth as a developer than that.”

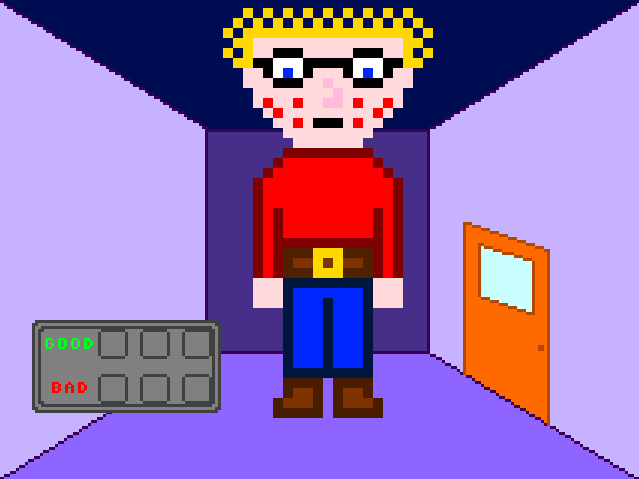

Last May, ExperimentalGameplay.com held a game jam based on the theme of “zoom”. Black submitted Intense Staring Simulator. The website describes it best: “a little depressing, but also pretty funny.” Intense Staring Simulator is an experience in the mind of a sociopathic teenager who hates people. His internal dialogue written with the amount of eye-rolling irritation toward society one would expect. When confronted by a stereotypical peer, be it a ponytailed otaku, or a awkwardly attractive teacher, he stares at the most embarrassing thing on their person to make them flee his personal space. Black admits the character isn’t purely fictional. “The nameless, misanthropic main character is sort-of an element of me; I get like that, sometimes,” he said, “Not to the point of hating humanity, or anything, but I think we all have days where we’re just not in the mood to deal with other people, and he’s basically that, taken to the extreme.”

Although it’s become secondary, Black’s screenwriting skills play a large part in designing his games. It doesn’t matter how simple they are, he has a story to tell. “I don’t think it’s a popular opinion in [game development] circles these days, but I genuinely believe that anything, if handled correctly, can be enhanced by a well-written, well-implemented story,” he said. Good writing will give context to the player’s actions, great writing will provide a compelling narrative to keep them playing. “It’s been said of me before that, if given the chance, I’d have designed Tetris to be plot-driven.”

He’s also familiar with the process of bringing ideas into reality.

“Having taken a full-scale stage production from inception of the idea to opening night, you learn a lot about managing resources, people and time. Most of the work I did at University revolved around taking an idea from a script and somehow replicating that in a physical space, which involved a lot of concessions, adaptation and adjustment, since there were a lot of resource limitations to get around. That’s a vitally important skill when you’re working on your own, or in a small team, because there will be things you want to do that you just can’t, for whatever reason, so you have to find a way to compromise that and somehow end up with something you’re happy with, even if it’s not what you originally envisioned.”

It’s been two years since Black’s sudden jump into game development. He’s learned a lot. Ask him the most vital part of learning to make games, and he’ll point to the game jams. “Ludum Dare is responsible for probably at least a thousand people deciding to make games who maybe otherwise wouldn’t, if there wasn’t such a friendly, open, flat-out FUN event like this to take part in,” he said. They force him to try different genres, and to follow through with the wildest of concepts. Like a game about a cake-hungry dinosaur with a jetpack, fittingly titled SADROCKETDINOWANTSCAKE.

It’s been two years since Black’s sudden jump into game development. He’s learned a lot. Ask him the most vital part of learning to make games, and he’ll point to the game jams. “Ludum Dare is responsible for probably at least a thousand people deciding to make games who maybe otherwise wouldn’t, if there wasn’t such a friendly, open, flat-out FUN event like this to take part in,” he said. They force him to try different genres, and to follow through with the wildest of concepts. Like a game about a cake-hungry dinosaur with a jetpack, fittingly titled SADROCKETDINOWANTSCAKE.

People who want to try making a game have a lot of easily accessible tools to choose from. “If you can’t program and have no desire to learn, there are so many tools that allow you to make games without a single line of code, like Stencyl, Game Maker, Construct or Multimedia Fusion 2, which is what I use. Each of them has dozens to hundreds of tutorials to get you from ‘Never heard of the program before,’ to ‘Just made a 10-hour 2D metroidvania by myself.’”

With that in mind, Black says there’s no excuse not to start now. “The hardest thing you’ll have to deal with is overcoming your own limitations, but there are so many options and tools for that, that it’s almost a non-issue. I, for example, can’t really do art at all, but that doesn’t stop me. I draw crude, representative art that gets across the point I want to make and then carry on with making the game. “

Black thinks he’s ready to give a “bigger project” a shot. He’s eyeing distribution platforms like Steam to start seriously entering the life of a “full-time, self-sustained game developer.” “The main problem right now is keeping myself afloat while I take the time to work on something good enough that I’d feel comfortable asking money for.”

He already has a few ideas. Whatever the project is, once he starts it, he’ll finish it.

No Comments