The Eighties were a terrific era for gaming on the PC. Back then, personal computers mostly functioned as gaming machines, with some lite word processing, calculators and spreadsheets thrown in for good measure. Actually owning a PC placed someone on a sort of tech/modern pedestal; the products were expensive, had limited use, and took up a lot of space, but were also still very rare. In fact, no one really knew if they needed one at all, as office life forced computers to be work objects, and typewriters sufficed at home.

My parents had wanted my brother and I to start early with home computers. My father felt that one day computers would be intertwined with our daily lives, and so he saved paycheck after paycheck as Christmas ’85 closed in to buy us one.

Except that I demanded he buy me an A-Z dinosaur book instead.

I was content with that pictorial encyclopedia — I was a bit of an 7-yr old dinosaur prodigy — and still have it to this day. The following year, though, our parents succeeded in surprising us Christmas morning with a premium, top of the line, Tandy 1000HX personal computer. No hard drive came with it, so all programs had to be booted from floppies or from the on-ROM DOS. If this nerd-talk has already gotten over your head, imagine what I felt like as a 8-yr old trying to figure it out.

Thankfully, there was one thing that we could understand: games. The Tandy, being an IBM-compatible computer, had plenty of them, and visiting Radio Shack every few months exposed us to a wall of cardboard boxes with images of dragons and poker cards on the front. But there was one box that stood out. It’s gradation from dark blue to darker blue was the home to a sea of twinkling stars, and was the backdrop to a familiar scene of a space ship approaching blocky letters that spelled out “Space Quest“. “Space” and “Quest”, two words that magically fit together and sparked the initial inner nerd fire. This was going to be the game for me.

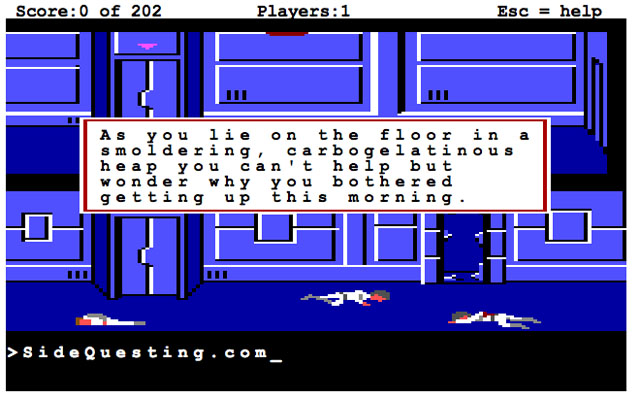

Space Quest, published by Sierra Online, is classified as an Adventure game: point and click to where you want to go, enter text to solve puzzles. I didn’t know that going in. The box art and description made it look like a wild action game set in the Star Wars universe. Robots, aliens, space ships, and janitors? Yes, please! Except when I brought it home, popped it into the 3.5″ slot of the PC, and was treated to Roger Wilco standing in front of a closet while a cursor blinked at the bottom of the screen, I was somewhat dumbfounded.

“Where were the aliens? Where was the shooting? Were there going to be ray guns?” As an 8-yr old, I didn’t realize that there was more to interactive experience than that.

“>Look computer.” That simple command is what started an obsession. Having used the keyboard to walk Wilco into an archive room, I typed that in while standing in front of the dark screen on the wall. As the process began, and I was able to access information and solve that initial puzzle, the genre’s mechanics quickly spread like a virus throughout my body, and I knew to “look” at things and “push” buttons. Eventually, I would “give money” to vendors to buy ships, avoid giant sand-dwelling monsters, and even interrogate bar patrons, getting drunk in the process — inverting the controls on an Adventure game made for many an awkward situation.

Adventure games required a completely different side of the brain to properly play and enjoy. It was less about physical problem-solving and more about blue sky logistics. Yeah, there could be an “unlock” button to solve everything, but actively typing in “put magic key into lock” forced me to think well outside of what I was used to. Adventure games by nature aren’t more than two – three hours long, but spread that out over a few months when you haven’t developed the vocabulary (or often, the adult humor) required to resolve situations prolonged the shelf life. They also have a knack for making us feel like we’re acting out scenes rather than jamming buttons.

Space Quest amazed me for the amount of things that I could seemingly do in the game, all related to text inputs. I experimented with phrases like “kiss alien” only to be instantly murdered. The same result came when I yelled at, punched, avoided, threw a rock at, or petted the creature. Eventually, I learned that I had to avoid it all together and walk around it. The amount of constant failure that came with classic adventure games got me to think creatively, and may have been a catapult for my career into an art-related, right-brained field. My brother and I would try everything, just to see what kind of reaction we would get from the game. “Smash xylophone.” “Feed zebra to robot.” “Tickle robot with rock.” Nothing made sense, but the occasional “Hey buddy, I’m not into that kind of thing!” reaction we received would be well worth it. This added to an already hilarious mix of janitorial humor, Star Wars homages, and self-referential jokes.

I have to admit: we never completed Space Quest without the aid of the magic marker hint book, a staple of the Sierra Eighties. When we finally did, and were witness as Roger Wilco saved the universe from Sludge Vohaul, we held the moment as high as any great movie ending we had seen. It happened in the little universe in my computer, and I was the actor.

1 Comment