Review scores. Sometimes they are a determining factor in a gaming purchase, helping a potential buyer choose between “mediocre” and “great” games. At other times they are sought after for marketing purposes or even reasons more sinister, such as if a particular sequel will be greenlit or a job lost.

Examining the reasons behind why scores are valued so much often leads to fisticuffs. After all, many a reviewer will say that the meat of the review process isn’t the score, but the text that accompanies it. A review is an expression of a viewpoint about a game, a summary of the experience and whether it is either good or bad or somewhere in the middle.

The score acts as a summary of that text. Yes, in effect it is a summary of a summary. And like a copy of a copy, a score can sometimes represent a ultra-minimal and deteriorated viewpoint without much in common with the review itself. Example: a 9.0-level game is viewed differently by different gamers. Would a 9.0-level puzzle game in Peggle, be considered the same kind of 9.0-level as a Halo 3? The review text may actually hold the correct score within its verbiage and speak to the right buyer, but the score represents something completely different.

In comes Metacritic, a summary of those arbitrary numbers which are themselves a summary of a summary. Confused yet? You should be. And if not, it only gets worse from here on.

We’ve been often told that Metacritic (as well as GameRankings and other review score aggregators) tells a fairly accurate story about a game’s probable rating, taking into account many of the most popular publications’ scores to provide a holistic industry average. While this may provide a more “solid” number, the flaws of the method become more and more apparent once several realizations are factored in. In the end this may prove to be a massive downfall to the system, in effect discrediting the final averaged score completely.

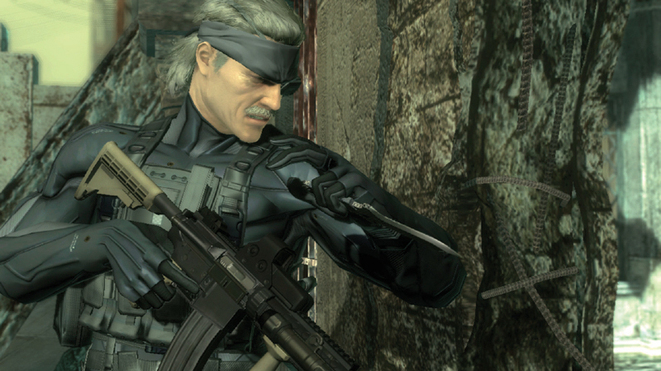

1. As noted above, scores are a summary of a summary. It is a summation of the review and not the experience, defined by a number or letter. Or, is it? An experience like Metal Gear Solid 4 was subjected to a considerable amount of reviews, detailing the positive and negative aspects of the game. Many reviews gave it a perfect score yet noted some flaws during the review. “Perfect doesn’t always mean perfect” was the common line. Apparently reviewers are not mathematically educated, as in my high school classes 100% meant perfect (as did A+ and 10/10). How can a review get a perfect score if it is not actually perfect? Essentially, the score (summary) is instantly biased towards the number instead of the text (summary). Perhaps an asterisk is needed next to the perfect score, much like baseball fanatics hope to place next to certain home run records. The average Metacritic number is then instantly skewed towards a score rather than an accurate representation of the game experience.

2. Not all review scales are created equal. With several outlets using unique scoring scales (G4TV‘s 5-stars, 1Up‘s letter grades, IGN‘s numerical values) it can be impossible to align those scores together to get a correct average. A recent incident involved a 3/5 score from GiantBomb translating into a 60% score for XBox 360 game The Ballad of Gay Tony. While the number 3 divided by the number 5 translates to 60%, the actual review score is to be read something more like a score of 70 or 75 out of 100. The inability of Metacritic to translate and compare scores between outlets becomes even more troubling when trying to deduce the letter grades used by 1UP. An A- for the game translates into a score of 91. However, what would translate into a 92? Or a 90? 1UP themselves have noted that their letter grades don’t translate well into numbers, as their relevance can shift based on quality. An A- for one game may mean something different for another. Metacritic doesn’t allow for this fluid grading.

3. The publications that Metacritic polls to create their numbers are often inconsistent. If Eurogamer doesn’t review a specific game, then the final score may be missing enough points to shift it from an 85 to… an 86. In order to have a consistent review score process, you need to have consistent reviews coming in. Missing one or two or three outlets begins to change the overall validity of a final Metacritic score.

4. A score from a site we do not follow may not mean much to us. If we value the reviews more from Joystiq than from MarioIsTheBestestGameEVAR.com then those should take precedence in our Metacritic score. Instead, the website parses reviews from gaming publications big and small, some that may be biased, and some that may not have any relevance to our likes. A review of Halo:ODST from GardeningMoms.com may not mean much to us, sadly.

So perhaps we all agree: Metacritic scores aren’t the most regular, valid, or correct translation of a an actual review. They are the one point meant to be added to the box art of an impending release, hoping to confirm to a potential buyer that the product is worth paying $60 for. They may make us feel better about buying a game, but if that game turns out to be one we don’t like then who do we blame? GardeningMoms.com’s 10/10 score for helping rate Cooking Mama 2 higher than Uncharted 2?

There are ways to fix this system, or at least help it come crashing down so that it becomes less important to companies who base entire marketing and PR efforts on it. With outlets inventing and reinventing their review scales on a regular basis it becomes increasingly difficult for Metacritic to accurately create a mean rating. In order for Metacritic to work, each publication would have to utilize the same scoring method (100/100, for example) and would have to review the same games. It may even do justice to poll based on writer than on outlet. Either way, forcing publications to all adopt the same system would create issues of integrity and pride that would create a headache far greater than the solution.

Several popular publications and blogs do not place scores on their reviews, like Joystiq, MTV, or even here at SideQuesting, pushing readers to actually read the text and understand the reviewer’s experience. And finally, we as consumers should find writers and gamers that we have similar tastes with, such as Ludwig Kietzmann or Jeremy Parish and stick to their reviews as a way to find games that may appeal to us more than those that Soccer Grandpa plays over at “The New York Oatmeal Revue”.

Whatever the case, Metacritic scores are increasingly becoming less helpful in discerning good vs bad games, or determining which games will sell or not (we’re looking at you, Dead Space: Extraction). Here’s hoping that Marketing Managers and Publishers realize the same.

Images courtesy: Konami, Rockstar Games, Majesco Europe

3 Comments